A tale of two villages

English Dance and Song Autumn 2022

This article appears in English Dance and Song, the magazine of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. The world’s oldest magazine for folk music and dance, EDS was first published in 1936 and is essential reading for anyone with a passion for folk arts.

Main image above: the former Cricketers Inn in Herongate

A tale of two villages: in search of Vaughan Williams in Essex

Library and Archives Director Tiffany Hore goes on the trail of Ralph Vaughan Williams in Essex villages Ingrave and Herongate – and finds inspiration for the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library’s upcoming conference on the composer and collector’s relationship with folk song.

I was a particularly geeky child who grew up in a rectory and donned a cassock, surplice and ruff almost as soon as I could hold a tune. In idle moments between the episodes of high-church liturgical pomp, I would flick through the appendices of the English Hymnal, my copy knitted precariously together by yellowing Sellotape: Index of Tunes – Heathlands, Heiliger Geist, Helfer Meiner Armen Seele, Helmsley, Herongate – how did they name these tunes, anyway? And so it came to pass that I knew the name Herongate (English Traditional Melody). One normally sang to it the popular Passiontide hymn, It is a thing most wonderful, imprinted on my chorister brain such that I rarely needed to glance at the page.

My young musings on tune naming were, on the whole, nothing more than idle. So, it wasn’t until I moved to Essex, just down the road from the village of Herongate, that I remembered the link. When Ralph Vaughan Williams accepted (somewhat reluctantly) the role of music editor for a new English Hymnal, published in 1906, he suffused it with tunes he had heard from the ‘mouths of the people’. Herongate was one such tune, notated by the 31-year-old composer from Emma Turner, a maid at Ingrave Rectory in December 1903, who knew it as In Jessie’s City. As if to maliciously disrupt the thread of this piece, he heard it not in Herongate but in Ingrave, the village next door (perhaps he named it thus because he had already called a tune Ingrave, no 607 in the English Hymnal, which I don’t think I ever knew). But as he was to discover, both villages overflowed with people who knew ‘the old songs’.

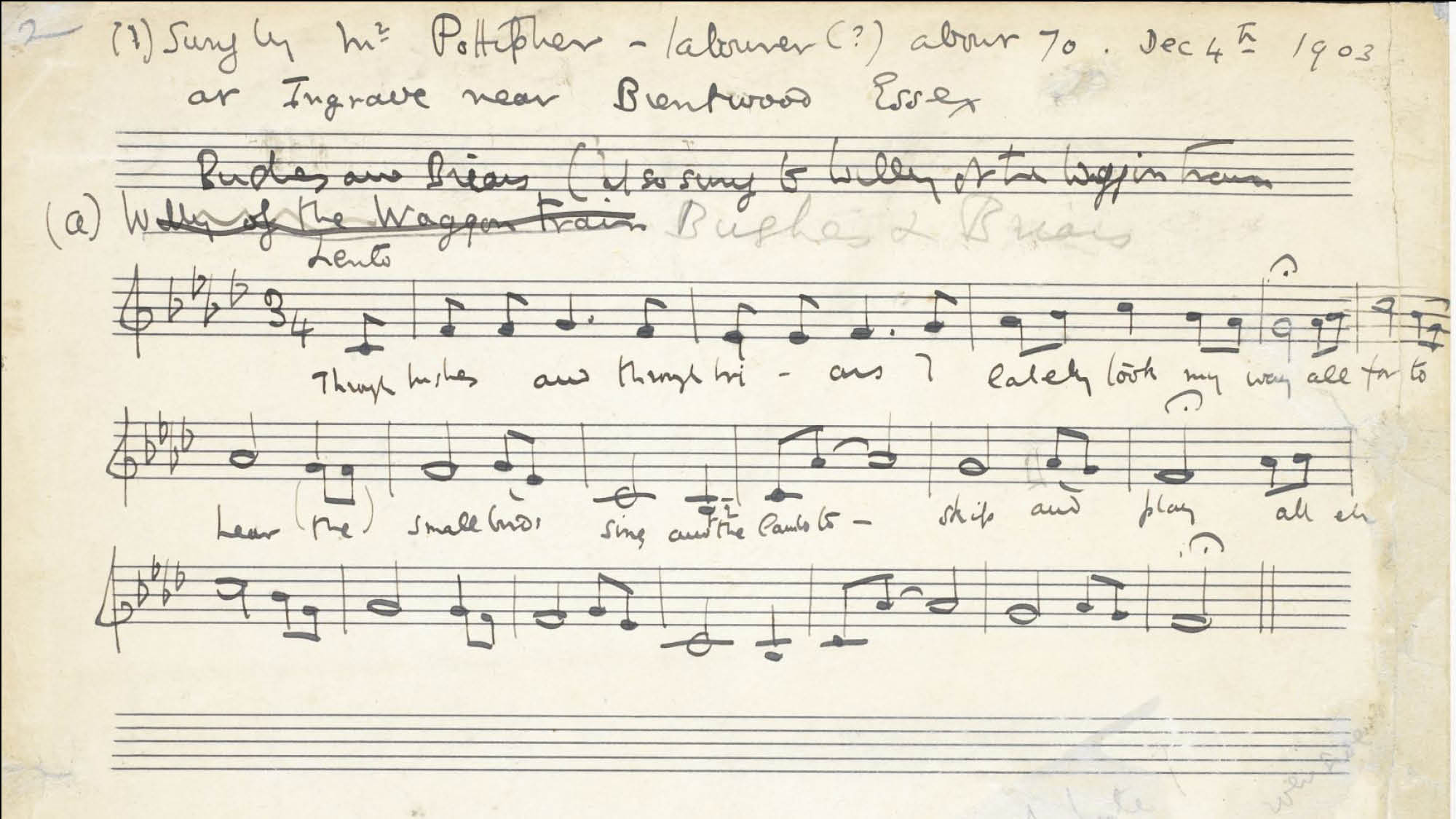

Ingrave, this pleasantly unassuming village near Brentwood, was the cradle of Vaughan Williams’ preoccupation with English folk song. It was here that he met Charles Potiphar, who sang Bushes and Briars for him and gave him sudden clarity of vision as to how he might fashion an ‘English music’. He was to collect dozens of songs in Ingrave and in Herongate between 1903 and 1906. I had cycled through these villages countless times but had never considered them through this lens, let alone stopped to seek the traces of their legacy. Armed with Frank Dineen’s book Ralph’s People: the Ingrave Secret, which had done the detective work (well, most of it) so I didn’t have to, I roved out on a hot July morning to put this right.

The clergy and their children

Being a musically inclined rector’s child, I was perhaps destined to end up working where I do, for the history of folk song is full of clergy and their offspring. Maybe as educated, highly literate and often musically trained members of rural communities, they were ideally placed to draw the attention of wider society to what their parishioners sang. Georgiana ‘Locksie’ Heatley, adult daughter of the Rector of Ingrave, invited Vaughan Williams to tea at the rectory in 1903, after meeting him at the Oxford University Extension Lectures he had given in a Brentwood school. She informed him that her father had invited the old people of the parish and that some of them may be persuaded to sing the songs they knew. However, Potiphar, the supposed star, demurred on account of the setting – instead inviting the composer to his home the following day. Ingrave’s old rectory, set in rolling farmland, is now a desirable private dwelling, appropriately named Heatleys.

Where it all began

Potiphar’s cottage is not the easiest to find, even with the help of Dineen’s book; it lies down an alley which itself branches off another alley, hidden from view by the trees. Vaughan Williams, we are told, found Potiphar wearing a smock, leaning against the timber door frame. Unlike at the rectory, a quarter of a mile away, he was at ease and prepared to sing.

Courtesy of the Vaughan Williams Charitable Trust

Graves, marked and unmarked

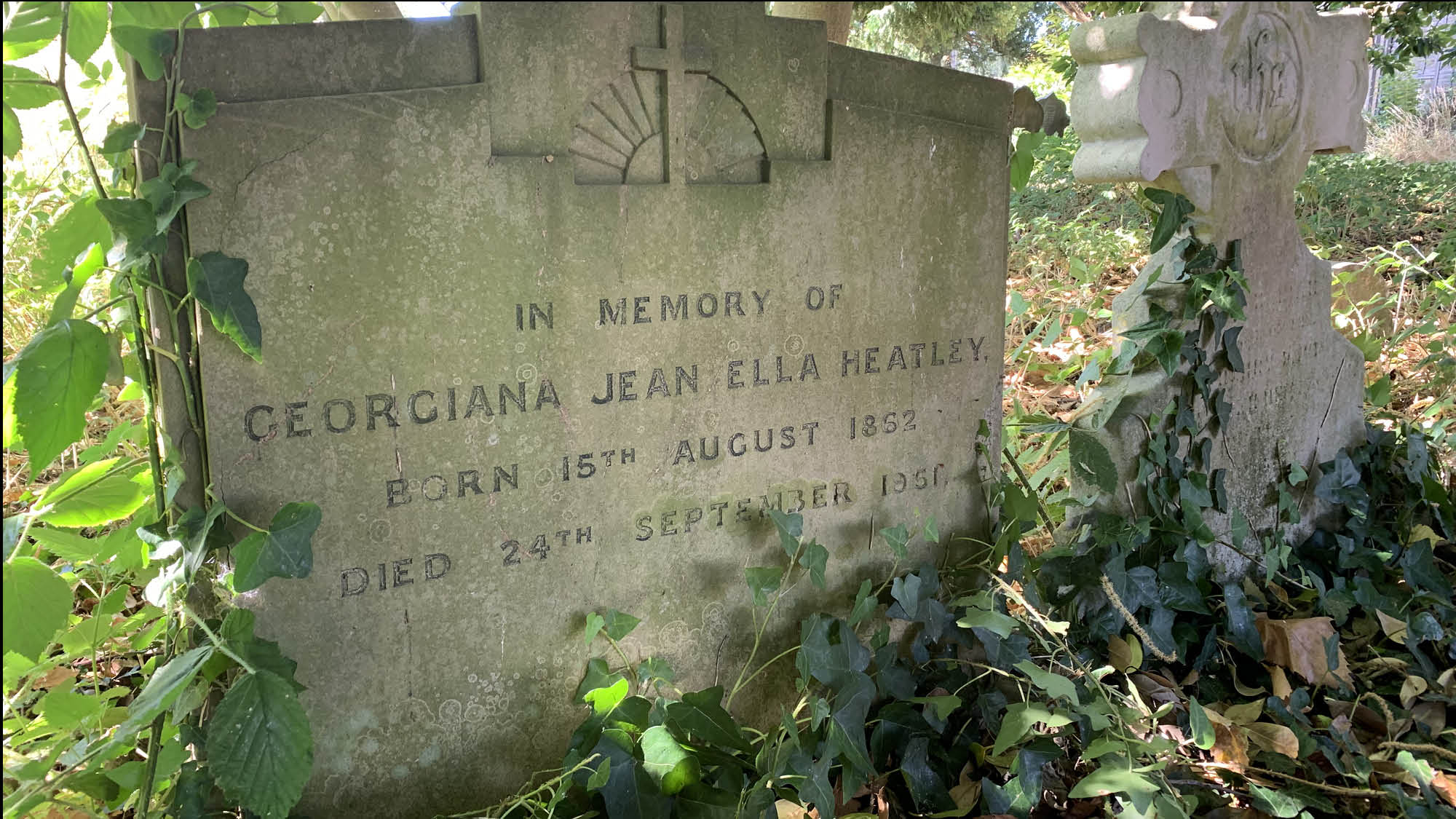

Georgiana Heatley, the clergy child of our story, outlived the rest of her family; unmarried, she lived out her life in the rectory until she died aged 89 in 1951. She is buried alongside the rest of the Heatley family in St Nicholas’ churchyard, in a plot it took me quite some time to find. Most of the rear portion of the churchyard is overgrown – and my sense of furtiveness

was not eased by a group of primary school children conducting a nature survey with their teachers a few metres from where I crunched my way through the bushes (and possibly briars). I eased the strands of ivy from the stone that carried her name; clearly, nobody tended the grave of the woman who facilitated the sea change in the career of the great composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. This seemed sad, but at least she escaped the fate of Charles Potiphar, who lies somewhere in the vicinity in an unmarked grave.

Fruitful collecting in two pubs

And so to Herongate, the hymn tune that turned out to be a village in Essex. I walked to it from Ingrave; in reality, they are a single entity now, welded together through decades of development along the A128 from Tilbury to Brentwood. Once one clears the petrol station on the crest of a rise, however, Herongate appears more stereotypical of the English village than its neighbour. It is centred on a cricket ground, surrounded by old cottages, one of which used to be a pub called the Cricketers Inn. Pubs, unlike rectory tea parties, proved a fruitful collecting ground for Vaughan Williams. It was at this watering hole, in both winter and spring 1904, that he listened to the singing of Jim Bloomfield and John Peacock.

On his spring visit, he heard from these same men again at a different pub, which is very much still a pub. Walking to the Old Dog Inn, which did not have the ‘Old’ attached in 1904, takes you out of Herongate proper, a mile or so down the road to Billericay. It is quieter than the main development, which makes it easier to imagine a time when the pace was less frenetic. As my feet crunched loudly across the pebbles in the empty car park, I felt conspicuous – more so as I tried the door, which creaked dutifully as if to fulfil the stereotype of the many storied old village pub. It was still closed. No chance of a cooling drink. I retreated with haste; what could I say if asked what I was doing? And what was I doing, anyway? Looking for a song, a singer, a legacy?

I’m not sure I can explain what I found in these villages, if indeed I found anything at all. But as I plan the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library’s upcoming conference on Vaughan Williams and folk song, I feel that my abstract thoughts on the subject have a tangible setting. Now, when I think of Vaughan Williams the collector, I imagine him walking up the Heatleys’ grand drive – and arriving at a far humbler timber beamed cottage down a secluded alley, his familiar face and form given a place. But who was Potiphar? What did he look like and what did he make of this encounter? We know it changed Vaughan Williams. Perhaps it even changed the course of English music.

But what of the man with the song? What of Emma Turner, who contributed quite unwittingly to the English Hymnal? I now have a frame of reference for my questions.

The conference, ‘Once more to the mouths of the people: Ralph Vaughan Williams and folk song’, will take place in November.